Hosted by: Hosted by:  (For the Greater Glory of God) |

|

The Message of Garabandal

Glenn Hudson

(Click with Edge; Right click to read aloud - Immersive Reader translate.) Glenn Hudson

(Click with Edge; Right click to read aloud - Immersive Reader translate.)

|

|

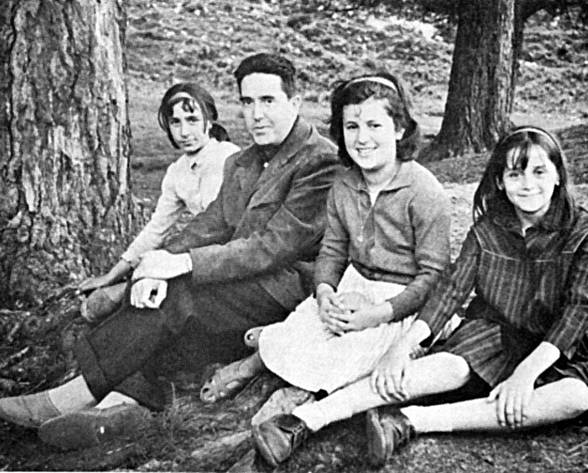

The Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in San Sebastián de Garabandal 013 Dr. Ricardo Puncernau, neuropsychiatrist Vice President of the Spanish Society for Sophronology and Psychosomatic Medicine and President of the Spanish Association of Para psychological Investigations. "I have weighed, thought about, and consciously observed [the events], and I have made the following conclusion: In Garabandal, there has never existed nor exists any other acting causing factor in relation to what is happening there except the Most Holy Virgin." During these times, in which the world is "confused" on the ecclesiastical level, similarly on international, social, familiar, and personal levels, full of injustice and egoism, we have dared to write these lines. These are a series of simple stories that deal with the famous happenings of Garabandal as seen through the prism of a Christian doctor. Since I am Christian, I am obligated to strictly tell the truth, without adornment, at least in the essence of the narration. What is important, I dare to say, is the adornment of the story. Barcelona, December 1974. Dr. Ricardo Puncernau.  Dr. Puncernau with Mari Cruz, Loli and his daughter Margarita at the Pines Since I am Christian, I am obligated to strictly tell the truth, without adornment, at least in the essence of the narration. What is important, I dare to say, is the adornment of the story. At least consciously, I haven't removed anything of what I remember. They are personal things, mine, as they relate to the history of Garabandal. They are things that I have never told before. Things that I believe are necessary to say. The next year, 1975, is the Holy Year. What better occasion to exhume events that seem buried forever, but that never have been in reality? It is evident that this has been written for those who already know the story of Garabandal. If not, I fear that they will not understand or value this testimony. Why did I make so many trips to Garabandal? Well, I don't really know . . . Garabandal is eight hundred kilometers away from Barcelona, where I reside and have my neuropsychiatry practice. My good friend Jacinto Maristany often urged me to go there. But I thought to myself: "I am not going to see hysterics, I already see enough in my profession as a doctor." Nevertheless . . . one night after dinner, he called me on the phone and told me (I didn't have my own car at that time) that Mercedes Salisachs, the writer, was leaving for Garabandal at four in the morning. She would wait for me with the car if I wanted, at the corner of Enrique Granados and Paris. I answered that I would think about it . . . maybe yes . . . but that if I wasn't there at four, not to wait for me. What made me get up at 3:30 to be ready at 4:00 to go on an adventure seeking hysterical girls? When we were going to bed, I told my wife about the pilgrimage. We knelt at the foot of our matrimonial bed to pray our short nightly prayers as we always did. When we finished, my wife opened the closet, took out the camera, and to my surprise, gave it to me, saying: - Take it . . . go to Garabandal and take a lot of pictures . . . That unusual gesture from my wife, who doesn't ever leave me, surprised me. How strange . . . ? - You can take Margarita along . . . Margarita is the oldest girl . . . She was about eight years old then. - But . . . - But nothing, you're going to Garabandal . . . Little Margarita was very happy about this unexpected trip. At the end, without 'frying it or digesting it' by 4:00 AM we were boarding Mercedes Salisachs's car and we embarked on the trip to Garabandal. It was the first of ten or twelve trips I made afterward. I still remember a hotel in Zaragoza where we stopped, and Mercedes Salisachs invited us to eat. We ate Cuban rice, one of my favorite dishes. In the afternoon, we continued on the trip with great speed and by sunset of that day we had arrived in Garabandal. How delightful the countryside was! How enchanting the pure air! The road with cars from Cosio to Garabandal was a disaster! The car slipped and then slid next to the precipice of a river. We ascended, with everyone pushing against the steep end, which was like the climb to Naranjo from Bulnes by the Northern wall, the most difficult. Once we had passed the two hundred meters of the climb, and since Garabandal was near, I decided to walk the rest of the way. The others stayed in the car until it became level. I walked, tranquilly enjoying the mountain scenery, calm after so much hard work with the car. They had widened the road a little and it was easier to navigate. To the left of the road there was a small rock that stuck out of the ground in a field and I saw a figure in white sitting upon it about three hundred meters away. Her mother was with her, but she had gone to cut or collect vegetables from a neighbor, or something. I saw that the girl was about thirteen or fourteen years old, maybe more, maybe less, and she looked at me without moving. It was, for me at least, a special look. I knew at once that this was one of the seers of Garabandal. I don't know how I knew, but I knew it. Her white dress stood out against the green grass of the field. Her figure seemed very kind to me on that afternoon; it was almost twilight, and it was the first contact I had with someone from Garabandal. It was nothing less than the most important person of the strange happenings that I had been told. The most curious thing is that after I met her, I told her that I had seen her in the field. She answered me in deliberate and sharp way, surprised: - I saw you also . . . I thought to myself, "Watch it doctor, do not let yourself be taken . . . " But the truth is that her answer surprised me. - "I also saw you . . . " I continued walking. I passed a curve in the road and I could make out Garabandal. Its houses were ancient and picturesque. In front of a type of plaza, underneath a solitary tree, was the parked car of Mercedes Salisachs. They accommodated us and put us in one of the farthest houses in the village to sleep; it was almost in the outskirts. It was a branch of the "Puncernau's hotel," as I will explain later. The streets of the village were illuminated by some weak bulbs and they made a true quagmire. They were full of stones and debris. When Mercedes Salisachs disappeared, I found myself; with no other than the sole company of my daughter, a little lost in the village. At the end of the main road in the village, I found Ceferino's tavern; he was acting as the mayor of the village at that time. One of his daughters, Mari Loli, was another one of the seers. Ceferino had gathered in front of the tavern with a group of friends. When we approached the group, the men looked at us suspiciously. Who are these people? I tried to strike up a conversation. When I told them I was a doctor, they stepped back a little. Obviously doctors did not have a very good reputation. Their reticence did not take away their amiability and good manners. Ceferino seemed like a dignified man to me, a little distrustful and sarcastic, but, like the majority of people in Garabandal, with a heart of gold. I still remember later on when we became friends he'd go to fish in the river for trout whether it was the season or not, and he would offer them to me. I have never eaten better trout than in Ceferino's house. After a little while, the rumor spread that Conchita had fallen into ecstasy. A little after that, so did Jacinta and Mari Loli. Then, finally, Mari Cruz fell into ecstasy. The four girls came together in a trance and prayed the Rosary with the people following behind them and answering. I took a quick look at the curious procession and I entered into Ceferino's tavern to drink a coca-cola. In the tavern there was a Uruguayan girl who had worked in the "Folies Bergére" in Paris. We started to converse. She told me that not only did she not believe in these supposed apparitions, but she also didn't believe in religion. She had come to Garabandal out of curiosity. After a while, I suggested we go outside to see what was happening with the seers. We saw them from a distance, crouched in the shadow of a house, and they were leading the Rosary towards the little village Church. From where we were hidden we saw what happened. Suddenly we saw that Conchita, in the trance, departed from the procession and started walking normally, but with unusual rapidity; she walked towards us even though we were hidden in the shadow of the wall of a house. She carried a small crucifix in her hand. I thought: she knows that I am a doctor and now she has come to "put on the show" for me. But how could she have seen me? But, no, she went toward my companion and put the crucifix to her lips to kiss three times. The Virgin Mary is also for the dancers of the "Folies Bergére." After this, Conchita's trance continued and she joined the other girls and continued praying the Rosary. My companion, the dancer, began to cry with great emotional sobs, so inconsolable that I thought she would have an attack. I accompanied her to the wooden benches that were outside Ceferino's tavern. People joined us and tried to calm her. Finally, she was able to explain that she had thought "in her mind": "if this is true that the Virgin is appearing, then let one of the girls come and give me proof." "As soon as I had thought this, Conchita came running to give me the crucifix to kiss. I didn't want it and I held back her hand. But she gave me the cross with such force and placed it to my lips, so that I had to kiss it. Once, twice, three times, and I am the incredulous one, the atheist, who doesn't believe in anything. This moved me tremendously." We met another time in a train on the return trip from Bilbao. I know, because she wrote to me a few times, that she later left the "Folies Bergére" and returned to her family in Uruguay. This was the first experience that I observed in Garabandal. My daughter Margarita came to me to say that she was tired. It was past midnight. I accompanied her to our room and I waited while she got into bed. I sat at the foot of the bed to keep her company, at least until she fell asleep. After a little while she said to me: - "Papa . . . if you want you can go . . . I am not afraid." - "Really?" - "Yes, go tranquilly . . . " I kissed her, wished her a good night and left her sleeping placidly. I went out to the narrow streets. It was a cold, starry night. The stars were shining for a Barcelonian visitor, with an unusual brilliance. I thought about whether it was true, that the Mother of Heaven looked over and protected the inhabitants and passersby in Garabandal with open arms. My children are not the fearful kind. Nevertheless, for a girl of eight years old to stay by her self so calmly in the outskirts of an unknown village did not cease to surprise me. Passing through the dark, solitary streets of the village, I also had this sensation of protection. Even with the quantity of people that had gone up to Garabandal, There has never happened, that I know of, a disagreeable accident. Once a truck full of workers fell off of a precipice into a river, but no one was injured: they only had a few minor scratches. And it should be pointed out that in those times the road was so bad it could have killed an entire army, no matter how motorized it were. I continued observing the girls' trances, but I refused to respond to the Rosary. It might be a fraud and I didn't want to collaborate in it. My role as doctor was to coldly observe the events. What premeditated coldness of heart could resist the amiable warmth of Garabandal? I found the seers in front of the closed doors of the little Church. They stayed there for a while, as though requesting an audience to enter. Then, without leaving the state of trance, they turned around and extended their arms in a cross. - "They are going to do the plane . . . they are going to do the plane." - I heard this murmured among the people who accompanied them. It seemed like a vulgar expression. But yes, with their arms extended they ran through the streets of almost the entire village. It was very curious because it gave the impression that they moved in a quick march, as though it was a movie in 'slow motion', like pseudo-levitation, but the speed was incredible, so fast that the boys of the village, young and strong, could not keep up with them, though they tried with all of their might. After running through the entire village they returned to a normal pace and then came out of the trance smiling. At this point we should address the entrance into the trance and their exit from it. They said that they had three calls. The first was like a "come," accompanied by a sensation of happiness, the second was a "come . . . run . . . come" with much more happiness and was much more urgent. The third call coincided with their sudden entrance into ecstasy. The girls would say, "Now I have one call," "now I have two calls." The spaces of time between the calls were completely irregular. Once, when I knew that they had already had two calls, I talked with them and tried to distract them and make them talk about something that interested them. Sometimes in the middle of a word they would suddenly fall on their knees in a state of trance, even though they seemed interested in what we were talking about. This drew my attention. It is not the normal way of entering into a trance if the person is not conditioned with a sign. Among the attendants no one was capable of understanding this or even knowing what it meant. More than once we had gone with Conchita to the pastures, to bring food to one of her brothers. Sometimes we shared meals with them. With Aniceto, we had gone until we could to see Tudanca from the highest point of the pasture. He had organized a stampede of wild horses that we could enjoy. During this, Conchita had stayed to prepare dinner. We all went on this excursion a little reluctantly; we would have preferred to have stayed at Conchita's side. We hadn't had enough of her company in the long walk; we wanted more. She was an enchanting girl. She was beautiful and playful, in the good sense of the word. She was intelligent and had a good sense of humor. She didn't have any prudishness or foolishness; she was completely normal. She was funny and kind, she was a lovable girl. I had seen many people, men and women, including priests, who were completely fascinated by her. She had an exquisite correctness, even with what could signify the slightest level of impurity. In general, the people were fascinated with her, and except for a couple of unfortunate performances, they always behaved with great appropriateness. There was an atmosphere of pure, immaculate Christian love; without stain. The same love as the Celestial Mother. On the way back, we would engage in all the imaginable childish games, and we laughed like fools, but I never observed a trace of unhealthy mischief. Perhaps this is why she was so attractive. We threw stones playfully and had competitions to see who was taller. We cheated and stood on our toes. In a moment, she could become serious and it was as though she was absent. It was as though she had some special internal life. This was the best way of knowing the girl, better than doing exams and tests on her, even though we did those as well. I can say the same about Jacinta, Mari Loli, and Mari Cruz. They were united by their Castilian or mountain gallantry, sympathy without limits. Once Mari Loli told me that when it started, she was sick because people followed her everywhere day and night and she could not leave them to use the bathroom in peace. Keep in mind that the whole village only has one "outhouse," or bathroom. As a result, no one can whine. Everything was simple and normal. I never did observe them attempting to "play little saints." And of course I will not cite the names for those disgraceful people who attempted to insinuate themselves maliciously to Conchita. Such insinuations were immediately cut off by the concerned person herself. It was curious to observe, as I said before, that everyone wanted to be in the company of these girls: men and women, the young and old, priests and laypeople. Without a doubt, this love was transferred to the Virgin, the one the girls said they saw and spoke with. But in many cases, such love did not transcend, but it stayed in the girls themselves, something that seems very human and natural to me. When Mari Cruz did not have an apparition and the other girls did, I felt sorrow, and I saw that she was sad because of it. I gave her my wedding ring so she could give it to the Virgin to kiss, as she was accustomed to doing. I stayed in Garabandal for three and a half days on that trip. The girl was very happy and put my ring on one of her fingers. Three days passed and Mari Cruz did not have an apparition; she didn't enter a trance. The night before the day I was leaving, I said: "you have to return my ring, because I am going to leave at three in the morning." "Leave it with me a little longer . . . maybe I have an apparition tonight." I left it with her. The other three girls entered into ecstasy. They walked in the trance with their arms linked. Mari Cruz went near them and took one of the girl's arms, lifted her head and walked ten or twelve steps like this to see if she would enter into a trance as well. But there was no trance. She unlinked her arm, very sad, and without saying a word, returned my ring and walked away with the head lowered. I must explain that my ring had already been kissed another time, in one of Conchita's ecstasies. I explain this to make the point that the ecstasies did come when it came . . . not when the girls wanted it. The transparent behavior of Mari Cruz could not fool anyone. I had given her the ring out of pure love towards the girl, because it pained me to see her sad. This was no scheme. On one of the excursions to the field, I stayed to eat because Serafín, Conchita's older brother, invited me. My son Augusto was invited to drink milk as it left the cow, but he couldn't digest it, or maybe it made him nauseated, and he vomited. He became sick and he went down to the village where my wife Julia was that time. I stayed alone with Serafín and we ate in the stable with the cows. After we ate, I tried to get him to talk, because it was a believed that he knew from Conchita when 'the Warning' would happen. I came to the conclusion that he did know, but did not want to say. The only thing I understood clearly was that the Warning would be preceded by a special event in the Church. After many questions and deductions, it seemed clear where it had been uncertain before, that it would be some kind of Schism; at least this is how I understood it. He told me that in the winter they pass entire months without going down to the village. I asked him how he passed the time and he said that he spent it thinking and reading some novels, from three to four. Serafín was a very kind and agreeable man. He was doubtful about what was happening to his sister. He repeated to me what Ancieta had said, that Conchita was very given to jokes, and that sometimes she could take it to the extreme. He gave however, the impression of being rather disoriented in the face of these unusual events. He was feeling like me, that as I had told Conchita, I "believed for five minutes, then doubted for five minutes." But be it as it were, what is true is that I noted religious fervor growing in me. When afternoon arrived, I went down alone towards the village by the way of the fields. I stopped a moment, where someone, I don't know who, according to Conchita had given birth to a child, Right there on top of a rock. I prayed a Hail Mary as I passed the slope where they sometimes had landslide of enormous stones, forming a sort of "river of stones." I crossed before the creek; I spent time contemplating the hard and wild countryside. And when I disembarked near Ancieta's house, there were the usual social gatherings at sunset time on the wooden bench adjacent to the house, with, whom else? Conchita. One or another clingy woman would always be holding her by the arm, as though She were a living relic. At the gathering you could talk about everything or about nothing at all. There were those who accepted the trivial, normal conversation, but there were others, among them maybe a priest, who did not stop prying and questioning, so that they could drive the poor girl dizzy. What saintly patience! Conchita's grandfather frequently sat on the wooden bench during these conversations. He was a kind, merry old man. Anyway, Conchita knew how to free herself from impertinent visitors and she would go up to her room or go out to play "jump rope." This narration has no more merit than within our human limitations, within what our feeling allows to know, within the true and correct use of the intelligence that God has given us, to tell the truth and nothing but the truth. I don't tell the whole truth because if I did, this story would be unending. Without other concern, I write unreservedly of the circumstances that I remember well and clearly. I write as a Christian doctor, but more as a doctor than a Christian. I hope that this does not scandalize any fanatics, as it has happened on other occasions. But what is truly worthy of observation and study, is that no one ever tires of talking about Garabandal. Furthermore, these chats, which sometimes are a repetition of the ones before, never grow tiresome and are accompanied by rare internal happiness for the one who tells them, and I dare to say, for those who hear them. My wife has heard many, many times, the same conference talk, and she tells me that she could continue listening to me her whole life. She listens to things that sometimes she knows better than I. I am a man that becomes extraordinarily annoyed when I have to repeat the same medical or paramedic conference. I avoid them like the plague. It is beyond my strength. Nevertheless, in dealing with Garabandal, I don't grow weary; it pleases me and gives me unusual happiness. It is as though I am drunk with happiness; not only during the conferences, but also in meetings or social gatherings. It is so much like this that we have to be warned, because if not, we will talk about Garabandal until three or four in the morning. The most curious thing is that it was an eternal "reiteration" of the same subjects. It was a curious enough thing. The devil probably also had something to do with this matter, because, a type of jealousy surged from this: from being the first to know a thing, or to enjoy a more intimate friendship with the girls, or to presume, something that wasn't true in general, to be in possession of some secret that was unknown to the others. Such presumption and jealousy were so stupid, that they could only be the work of 'the Tempter.' But what is certain is that I have given about ninety conferences about Garabandal, most of them with graphic collaboration from David Clúa, without being tired of it. And I always had to shorten them, because if not I fear that the conferences would have become interminable and overwhelming. I would limit myself, as I have written, to the most important facts. This care towards all that refers to Garabandal would be automatically extended in a spontaneous manner to all followers of Garabandal, except half a dozen fanatics, who with good faith I'm sure, would often overstep the boundaries. With the motive of a brief essay that I wrote, in which, to demonstrate the little appreciation we had for the things of the Mother, it occurred to me to put an ink stain inside it. They wrote me ferocious letters, improper for Christians, which I still have. And this in the name of the Virgin! But apart from this little group of fanatics on the fringes, the rest of the Garabandal followers seem to me very sensitive and very good, who believed in the events without any doubts. Not to mention the people of the village, who In spite of their suspiciousness ("no one is a prophet in his own land") and doubts, but they were such good people, that I would have loved to live with them. In this task of promoting Garabandal, later on Dr. Sanjuán Nadal helped us on his part. I made the second trip to Garabandal with my wife and oldest son Augusto. My wife remained disillusioned about what she had seen in Garabandal, because it seemed worthless to her. My son Augusto, who was very serious and steady, didn't say anything. My wife Julia gave her wedding ring to Mari Loli while she was in ecstasy so that the child would give it to the Most Holy Virgin to have it kissed. Since her finger was swollen and it wouldn't come off, the girl took Julia's hand and turned it so the Virgin could kiss the wedding ring "in its place." I repeat that it seemed childish and weak to her. Nevertheless, in one of the races that the girls used to make to the Pines, (and of which I will speak about later,) in front of the Church door where they had come to a stop, as they were accustomed, it occurred to Julia to touch the cheek of one of the girls (I think it was Mari Loli's) and while we were all sweating and tired, according to the happy comment of my wife, Mari Loli's cheeks were like "a peach that had just been taken out of the freezer." As I said, the first time I went alone (with little Margarita). On the train between Santander and Bilbao, I met the same girl from the "Folies Bergére." We sat together and began to chat about non-transcendent things. During the course of the conversation, since I was very warm, she offered me a paper tissue full of cologne to refresh my arms and forehead. Even though I do not like perfumes very much, I accepted and I passed it over my arms and hands. We said goodbye in Bilbao, and we exchanged addresses and began to write each other about Garabandal. My daughter and I had a three hour wait before taking the express to Barcelona and so we decided to go for a small walk in Bilbao. At the scheduled time, we boarded the overnight train wagon and went to eat at the restaurant wagon. Everything was new to Margarita, and she enjoyed it greatly. It was during the dinner that I began to notice the smell. It seemed to come from my left arm and hand. At the beginning, I attributed it to the cologne from the dancer at the "Folies Bergére," and I didn't think about it. In our compartment I noticed the smell again. Then I realized that it came and went in spurts. It was very intense, like sandalwood. It only smelled on the left side. This lasted for about two minutes, and then it disappeared. It didn't have fixed intervals. I said to myself that it was the power of suggestion, that I shouldn't say anything to Margarita. I recognized that the next gust of strong fragrance was coming from the ring that had been kissed by the Virgin. At least that is where it smelled the strongest. Interiorly I was ashamed of myself for letting myself get overtaken by this suggestion like a hysterical person. I didn't say anything to anyone, but the gusts of sandalwood odor (at least that it what it seemed to me) became very intense little by little, in the moment least expected. The next day, the strange fragrance was repeated at irregular intervals. It was very strong. When I arrived at home, we took some time to collect ourselves a little and then we got on a train to Caldetas, where my family spent summers. Finally, I secretly told my wife about the fragrance. Naturally, she thought I was crazy. Nevertheless, that same night, when we were already undressing for bed in our room, the fragrance came. I put my hand next to Julia and I said: - "Take it now, smell it . . . " She took my hand just to make me happy, convinced that I was mad. I put the ring to her nose and when, according to her, she was going to tell me: - "But I don't smell anything . . . " I saw her become pale like the white wall in our bedroom, and she was unable to articulate any words because she was so overcome with emotion. - Well, yes . . . yes, it smells . . . like sandalwood . . . The next day when we were on the beach, the fragrance returned stronger than ever. I was surprised that people did not come to ask me what it was. My son Augusto was at the edge of the water with me. Take this and smell it. - I told him yes. - He answered with his habitual seriousness: - Yes, this smells . . . I don't know of what, but it smells very strong . . . He didn't pay any more attention to it and he went into the water. That was the last time I perceived the strange fragrance. After that, It never happened again. In spite of the fragrance, my wife continued with her doubts until an unusual phenomenon happened, which I will relate later. Julia, my wife, only went to Garabandal once. Fr. Alba, my son Augusto, Señor Serra, and a magnificent driver, Señor Pedro, came with us on that trip. Fr. Retenaga never came with me, nor did Dr. Ortiz ever observe any medical evaluation or exam that I performed on the girls. I want to make clear that Dr. Celestino Ortiz Pérez has always merited my respect, confidence, and sympathy. The only thing I would say is that he is excessively emotional. Such emotion is a product of his natural goodness. Julia returned disillusioned from that journey. It seemed to her, as it later did to the famous Bishop Puchol, a game of children, without the least importance. The rest of the family was in Caldetas for the summer. Julia immediately went to Caldetas without making a stop in Barcelona. I went up the following Saturday. I was very surprised when I found that she was completely changed with respect to Garabandal. She told me that the day before strolling in the middle of the afternoon through the lush municipal park in Caldetas, with its hybrid banana trees, and in the moment least expected, she felt absent from reality and moved to relive everything about Garabandal. It was as though she was sleepwalking, and as though the people and things in the park were unreal. All of this, with great certainty about all of the things of Garabandal, caused an immense growth in her love for the Virgin, with a security and very vibrant emotion. - "I have always loved the Virgin . . . but what do you want me to tell you . . . but now . . . " - she told me. This state lasted a few instants in calendar time and much more in internal and psychological time. From that moment she was convinced of the truth of Garabandal and everything it meant and was. She was convinced and she continues that way. She always has been . . . She has never had any doubt. Never. Next to this, there was a notable increase of the spiritual love in our marriage, accompanied by a strange sensation of internal happiness, which I dare to qualify as otherworldly. There is only one point I want to emphasize here. I have weighed it, thought about it, and observed it consciously, and I have come up with the following conclusion. In Garabandal there has never existed nor does not exist, any other causing agent acting there than the Most Holy Virgin. The Most Holy Virgin Mary is for believers and non believers. But of course there is no human cause, no person acting in such functions, nor closely nor remotely. At the time of writing these lines, I am Vice President of the Spanish Society of Sophronology and Psychosomatic Medicine and President of the Spanish Association of Parapsychologic Investigations. So, I do understand about these things. In Garabandal, it is necessary to be humble. I had arrived in the village that same afternoon. I had the intention of examining Conchita, not only from a neurological point of view, but also from a psychiatric point of view. At the latter hours of the afternoon, I went to Conchita's house; this is the time when the girl is usually there, not to perform the examination, but at least to schedule it for the next day. Everyone has the right to be in a bad mood sometimes. I entered the kitchen to explain my purpose to Conchita. But as soon as I began to talk, her mother Aniceta told me to leave; without too many words. I was stunned and left. Nothing like this had ever happened to me. Aniceta and Conchita had always treated me with very good manners. As I will explain later, I had already examined the other girls and I had spoken with Conchita about examining her as well later. I went to have supper; we had the usual tortilla and a little sausage, and then I went back to the "Puncernau's hotel," which was what we jokingly called the house. It was the first house on the Main Street, and it was the property of two brothers, who were filled with goodness and sincerity. I can't deny that after this fiasco with Aniceta, I was in a bad mood. Later, I became more serene and I thought that if all of this was from God and if it is meant that I could examine Conchita then it will be done, and if I couldn't make the exam or it wasn't from God, then an exam wouldn't make a difference. That is, I accepted what God gave with humility. I slept very well. After my breakfast of a great coffee with milk, I set out to go for a walk around the town, without a fixed route. On one of the streets, I ran face to face into Aniceta. - "What did you want last night . . . ?" - "To examine your daughter . . . " - "Come with me . . . I think she's in the house now . . . " We went to her house. - "Conchita . . . Conchita . . . Dr. Puncernau wants to examine you." "It is probably in your own room . . . down here they would not leave you alone. . . . Go up, doctor." Conchita had placed two chairs facing each other at the side of her bed. We left the door open. Aniceta rummaged around the house and sometimes she came upstairs to look for something and to watch what we were doing. She didn't say a word. - Before anything else, take off your shoes and sit on the bed. She was quickly rid of the type of canvas sandals she wore. I want to remark that she had clean feet; the feet and the legs. I examined her reflexes, her balance . . . the external sensibility and internal, the motor system, the cerebellum, the cranium, etc. Then when she was sitting in the chair, I finished the neurological exam. Afterwards, I did a Koch test and a Rorschach test. To summarize, I did everything having to do with her mouth. In the Rorschach test, I was surprised because she did it at a great speed and gave more than 70 responses, which were completely logical and they included a lot of movement. She had a vivid imagination and a tendency to fabricate. The Wechier-Bellvue test reported a score of superior intelligence. To my great delight we were together in her room for more than two hours. After awhile, at a moment I was silent, she asked me: - What are you thinking about, doctor? I responded in a spontaneous manner: - I was thinking . . . that it is a delight to be here with you . . . There was not the least shadow of an ill thought in my response. I responded simply with the truth, and I don't regret it. Her eyes, a little playful and joyful seemed to say to me: "Don't take it so seriously, doctor" But the truth is that it was a pleasant experience being there, very pleasant. The foretold doubts and denials of the seers themselves are well known to the Garabandal followers. How can one proceed in the study of this? The first problem that we should consider is to treat the explanation as it presents itself in simple terms: a) It all had been a simple children's game. b) The girls repented of their game and have finally confessed the truth. The first affirmation is unacceptable because of medical studies. Even in the case that the girls could have added "something" of their own making; it is very improbable that ALL of it was the children's game. The very same doctors named in the assigned Commission, in my understanding, had sufficient scientific expertise to discover a childish trick from the first moments. Those states of ecstatic trance, with the loss of sensibility and their senses, the abolition of motor reflexes and blinking, the muscular plasticity during the trances, the resistance to fatigue, the exact changes of emotional expression in the faces of the four girls at once (without any contact) in the same instant, etc., etc. cannot be considered a game of children. The medical history of the events of Garabandal, from which there is an abundance of graphic testimonies, is incontestable. On another of my trips, I was in Santander with the kind secretary of the Commission. We spoke for ten hours and we went over all of what he considered to be negative with respect to Garabandal. As a result of this study, it was agreed to go see the Bishop's representative (the Bishop was at the Council), in order to request the formation of a new Commission of Study. The Vicar promised us he would communicate our petition with the Bishop. However, as far as I know a response was never received. During one of my visits to Garabandal, I asked permission from Mari Loli and Jacinta's parents to lift the girls during the trance. They didn't have the least objection. I lifted Mari Loli and Jacinta separately. They were kneeling when I did this; I lifted them holding them by their bent elbows. I noted a marked plasticity of their muscles. The people had told me before that when the girls were in a trance, no one could move them or lift them, even though people of considerable strength had tried. I have an ordinary amount of strength, more or less. Nevertheless, I lifted them a few inches off the ground with great ease. If it were not because in those moments the power of suggestion can play tricks, I would ascertain that they weighed less in the normal state. When they were back in the normal state once again, I asked them to get into the same posture. I had the impression that it took much more effort than when they were in a state of trance. I could assure that there was a considerable weight loss during the trance. Now I should confess that I played a small trick. Without losing my medical rigidity and lucidity, I prayed a Hail Mary with all Christian fervor before my attempt. This was my trick. The other day, I asked Conchita's family if I could stay with her the entire time if she had a walking ecstasy. There was no objection. That afternoon, I had announced to Conchita my intention of examining her. It seemed that the girl was a little worried. During the course of a long trance, walking through the streets of the village, I heard her murmur my name clearly. - "Is it good of Dr. Puncernau?" - "Well . . . but that will be of little importance . . . " This was part of the conversation with the vision that I overheard. When she finished the ecstasy (there were many people) I asked her to tell me what the Virgin had said about me. I didn't have everything. I thought to myself, "what if she begins telling all of your sins." As if though Conchita guessed my fears, she said: - "The Virgin never reveals the sins of anybody" . . . In a moment when they left her more at peace, she wrote the following on the back of a holy card, which I naturally kept: (textual copy) "The Virgin told me that she was very happy with you because you are giving much glory to God. What you are studying will happen and you will succeed. Conchita." The superlatives called my attention. "This must be a thing coming from the child herself." But, what Mother doesn't find all of the graces in her child has even if the child were a notorious person or a shameless one? Another detail that I want to relate is the following. Frequently during their ecstasies, the girls take off their shoes and walk through the streets which are full of mud, stones, holes, glass, animal droppings, etc., etc. Although I have not personally witnessed it, they assure me that they have passed barefoot over a pile of burning coals that were spread. That day, when I knew that they had two calls, I begged Conchita to let me examine her feet. She took her old sandals off both feet. I observed the bottom of the feet especially. They were clean; there was no mud on them. Maybe she had just finished washing them. I don't know. She had a long trance, and in the middle of it, she lost her sandal and continued walking with one bare foot. I observed that after awhile she removed the other sandal during the ecstasy. She walked through the streets of the village for awhile. She passed through the streets over all of the mud and other debris in her bare feet. She finished the trance barefoot in her house. Immediately, I asked her to let me see her bare feet. I looked for a scratch, a cut, a contusion on her feet. There was nothing. When I was tired of examining her feet, she put her sandals on once again. Until later, I didn't realize one essential fact. Her feet were as clean as before she had walked through the muddy streets. I knew she hadn't cleaned them. I am sure, because she did not leave my sight. She had not even gotten her feet dirty. There are many, many things to tell about Garabandal. The majority of things are found in numerous books and pamphlets, which have been written about Garabandal and its protagonists. I said before in this short report, that I have separated what affects me as a medical doctor from what affects me as the Christian who loves the Virgin Mary. They are two separate parts. A few days ago, I learned of Ceferino's death. May Ceferino rest in peace. He was a man full of brute strength and sincerity. He was the one who told me the following: "It was winter. There had not been any visitors in the village. There had been a blizzard, and it was very cold. Around three in the morning, I heard Mari Loli getting up and getting dressed." - "Where are you going now . . . ?' - "The Virgin has called me to the cuadro . . . " - "Are you crazy, in this cold . . . ?" - "The Virgin has called me to the cuadro . . . " - "What if you encounter a wolf . . . do what you want . . . but neither your mother nor I are going to accompany you . . . "Mari Loli finished dressing, opened the door of the house and went toward the cuadro, about two hundred meters away from the village. If I had been sure it was the Virgin, I would not have moved from the bed . . . the Virgin would have cared for her . . . but since we weren't sure, my wife and I got up and walked toward the cuadro. We found her in the middle of the blizzard, on her knees in a trance. It was freezing. We thought she would be as cold as ice, so we rubbed her cheeks. She was very warm, as though she hadn't left the sheets of her bed. We stayed there for more than an hour. We were dead from cold. All the while, she continued speaking familiarly with the Vision. Obviously, the penance was meant for us, the parents . . . " This is what Ceferino told me, more or less, one night when we were sitting in his tavern. I repeat that if I had to write everything I lived in Garabandal, it would be a book the size of Dr. Zhivago. This isn't my purpose. The majority of events in Garabandal have been written abundantly in national and foreign literature that has been published. I only wanted to mention a series of events that were very personal and I haven't mentioned until now, except to very few people in my family. I have waited fifteen years. Naturally, thanks to God, I am a man who has Faith. Faith is rooted in the observation of history, among other things. Every time that explanation questioning Religion has surged, I have observed that with a little time and patience, soon a new explanation comes to put down the opposite prejudices. I recognize that I have would have preferred to write these previous pages, from the perspective of the Christian faithful, but this is not the paper that has been assigned to me. I have written them with all of the detachment possible and above all, with absolute sincerity. |

Last Update Dec 18, 2025